Bruce’s Bones: the discovery of Robert I’s grave in 1818 and its political and cultural impact

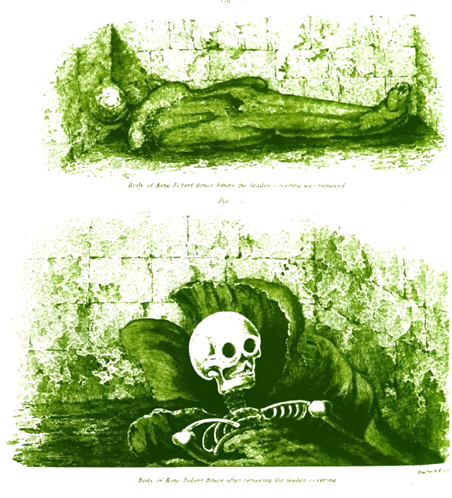

On 17 February 1818, workmen clearing the ruins of the abbey choir of Dunfermline, Fife, uncovered two large slabs and, beneath them, a shallow stone-lined grave containg a lead shrouded skeleton. Given the central church position of these relics, almost all contemporaries believed this to be the burial site and mortal remains of Robert Bruce/I (1306-29), whom later medieval chroniclers had described as being buried ‘in the middle of the choir’.

News of this great discovery quickly spread and, according to local annalist, Ebenezer Henderson (1855), was soon ‘all the talk of the town’, just days after the ‘discovery’, too, in Edinburgh Castle of the Scottish crown jewels. However, the authorities in Fife, Edinburgh and even London became increasingly fearful that such a potent icon as Bruce could become a rallying point for radical and even violent agitation for political and socio-conomic reform across Scotland in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars.

This was the starting point of a research project (2005-09) to investigate the contemporary political and cultural reaction to the recovery, inspection and ritual re-interment of ‘Bruce’s bones’ c.1818-20. This revealed much of the complex cross-currents of local and national political tensions of the day. It also revealed the important role of many individuals and collective view points in contesting the remains and memory of this great Scottish historical figure and site, and in thus shaping Scottish affairs and identity: from the ordinary folk and officials of the burgh to such key figures as Walter Scott and Lord Chief Commissioner Sir William Adam of Blair Adam (both members of the ‘Blair Adam Club’ of history buffs), Attorney General Sir Samuel Shepherd, and even Thomas Bruce seventh Earl of Elgin (of Elgin marbles fame and nearby Broomhall House). Not least, understanding this context explains why:

- the Bruce remains were inspected and re-interred on 5 November 1819, a Protestant double-holiday marking Guy Fawkes Day and the anniversary of the Hanoverian landings of 1688.

- crowds of ordinary citizens of Dunfermline were only reluctantly admitted to view the bones.

- many relics from the grave were souvenired or stolen on that day.

- a small group of locals fabricated a Bruce name plaque and hid it in the grave debris.

- it would take another 70 years before the Bruce’s grave was properly marked by a brass plaque donated by the Earl of Elgin, not the Government, which also reneged on its promise to secure and mark all royal remains within the new Abbey Church.

The findings of this research have been published and can be dowloaded as:

“Memorial to Battle of Bonnymuir” by Lairich Rig is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

This work led in turn to further research which evidenced a link between the authorities’ fears about such historic figures and sites as Bruce, Bannockburn and Dunfermline, and Scotland’s ‘Radical War’ of 1820. This included an armed attempt by radicalised workers to seize control of Carron Iron Works near Falkirk about 6 April, the anniversary of Bruce’s 1320 Declaration of Arbroath:

Both these projects illustrate the great wealth of archival material embraced within local authority, church and civic society records which bear upon the complex political, social and cultural construction of Scotland’s oft-disputed past, heritage and identity.